The Process of Tracking Changes to Our Bibles

Last post we noted that there should be some sort of central audit for noting all changes made to each edition of every major English Bible translation, especially in light of changes made to the New International Version (NIV 2011), English Standard Version (ESV 2016).

[T]he process of converting printed editions of the Bible into digital ones is time-consuming and requires careful attention.

To start that process, I recommend that we should make available digital copies of each text edition. That’s not difficult for editions made in our era of desktop computing (e.g., ESV, HCSB, NIV 2011, et al.). But that’s a challenge when some of our more popular editions were photo-typeset before the proliferation of computers (e.g. NIV 1973, 1978, 1984; NKJV 1979, 1982, 1984; RSV 1946, 1952, et al.).

It’s challenging for two reasons: First, many Bible publishers do not make digital copies available for editions no longer in print. (There’s no need to when there is no demand for such.) Second, the process of converting printed editions of the Bible into digital ones is time-consuming and requires careful attention. Here’s how that process now works:

Digitizing Printed Editions

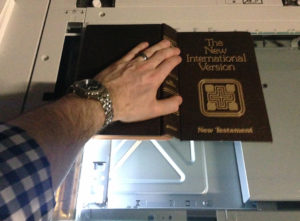

Since I work at a local print and copy center, it’s convenient to scan printed pages of the Bible into raster images after work-hours. For example, let’s start with an early printed edition, such as The New International Version New Testament (1973 ed.).

Then we place each page on the scanner’s glass and make a scan, which is stored and collected into a digital file.

This results in a Portable Document File (PDF), which we can view on a computer screen.

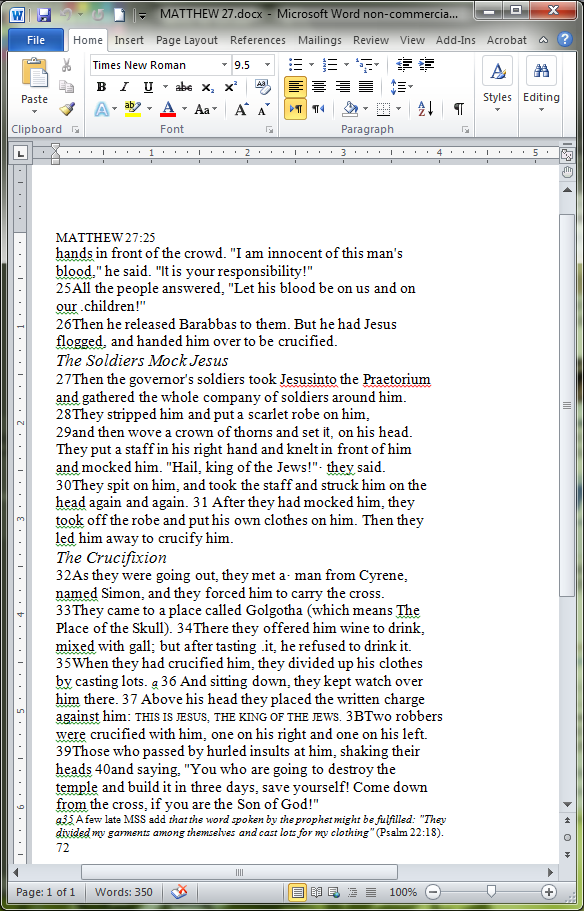

My software will then recognize the letters on each page and give us a digital text in a process called Optical Character Recognition (OCR).

This allows us to digitally “copy” and “paste” the text into a word processor in order to “clean it up”.

The next step is to “clean up” the text from all the blips and blurs that the OCR process couldn’t ignore. We can use industry-standard desktop software for this process because of its familiar workspace and advanced search-and-replace features. As you might imagine, this is a very tedious process: There is no way to eliminate distracting dust and scratches except to manually edit all the pages while comparing them to the original scans. This way we ensure that the digital text is free from corruptions.

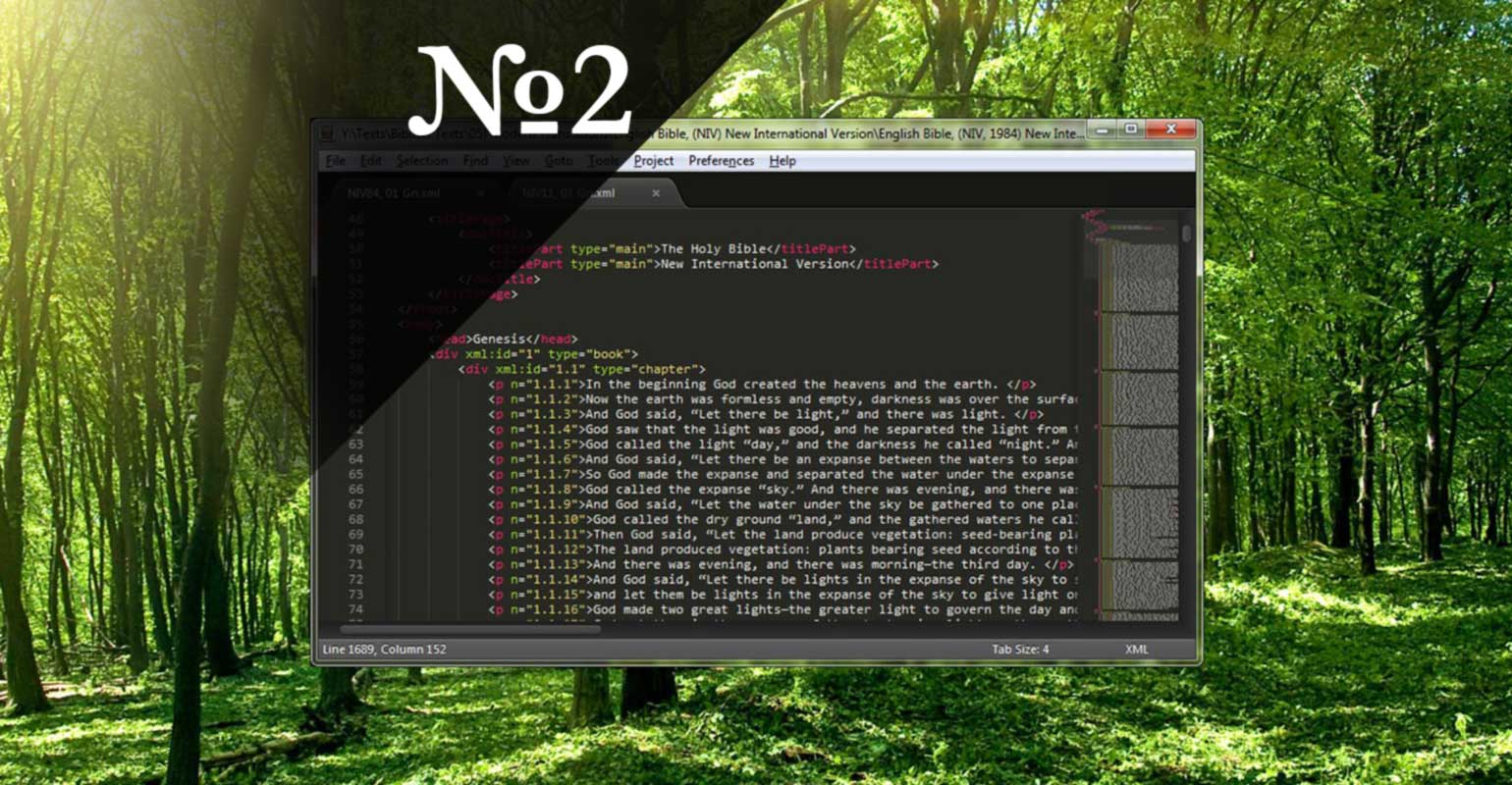

The following step uses General Regular Expressions (GREP) to format the text in a machine-readable way in order to automate the process of contrasting the changes within the various editions of the Bible. When biblical texts are already in digital formats, like most modern editions of later translations, we can bypass the scanning and cleanup altogether and jump right into formatting the text into eXtensible Markup Language (XML).

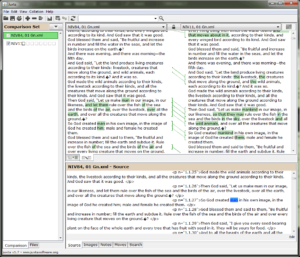

We’re almost there! The next step imports two editions of the Bible into text collation software and highlights the differences found between them. From here, we can generate a critical apparatus which concisely lists the variations side-by-side.

Where From Here?

As mentioned in the previous post, some publishers and individuals have already made such collations of changes publicly available through their websites. This does not include all editions of all major English Bibles, neither does this include independent audits of those changes (with the exception of the NIV 1984, TNIV, and NIV 2011). The end in mind is a full central audit for all textual changes between all editions of all major English Bible translations. Our destination requires a long, arduous journey, where we repeat those steps laid out here for each edition. I’ll keep you posted with each new edition’s collation and any related news.

Leave a Reply